Hemochromatosis (Iron Overload)

What is Hemochromatosis ?

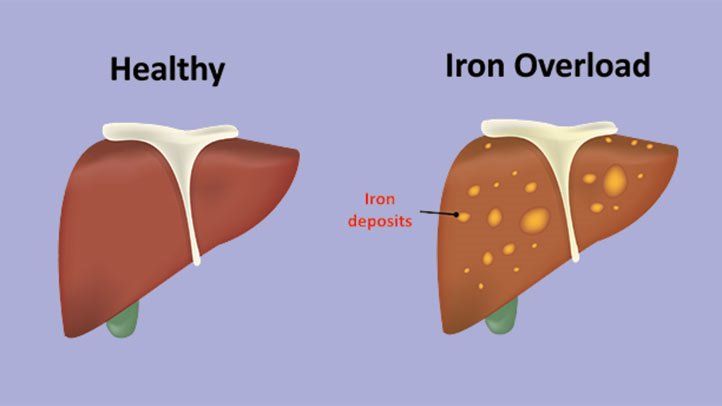

Hemochromatosis is a hereditary disease that disrupts the way the body metabolizes iron. Normally, when your body detects that it has sufficient iron in the blood, it reduces the amount of iron absorbed by your intestines from the food you eat. So even if you stuffed yourself with iron supplements you wouldn’t load up with excess iron. Once your body is satisfied with the amount of iron it has, the excess will pass through you instead of being absorbed. But in a person who has hemochromatosis, the body always thinks that it doesn’t have enough iron and continues to absorb iron unabated. This iron loading had deadly consequences over time. The excess iron is deposited throughout the body, ultimately damaging the joints, the major organs, and overall body chemistry. Unchecked, hemochromatosis can lead to liver failure, heart failure, diabetes, arthritis, infertility, psychiatric disorders, and even cancer.

Symptoms of Hemochromatosis

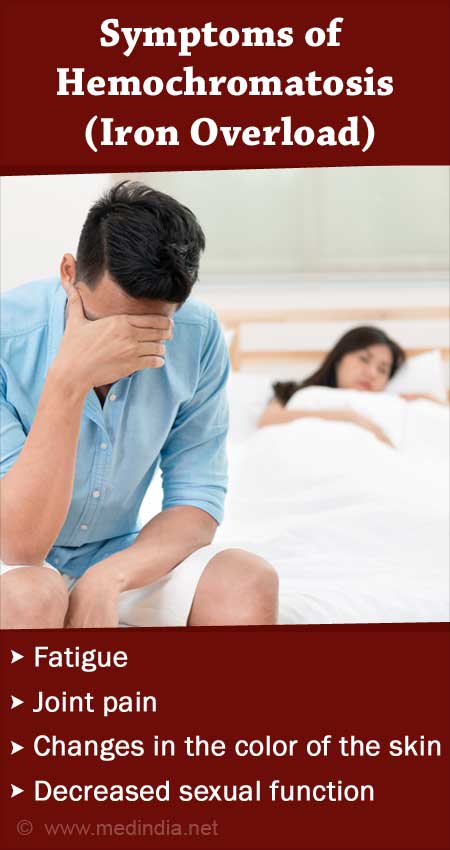

Many people with hemochromatosis don’t have noticeable symptoms. When symptoms do exist, they may vary between individuals.

Some common symptoms include:

- fatigue and weakness

- weight loss

- a low sex drive

- abdominal pain

- bronze or gray skin color

- joint pain

History of Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis is caused by a genetic mutation. Recent research has suggested that it originated with the Vikings and was spread throughout Northern Europe as the Vikings colonized the European coastline. It may have originally evolved as a mechanism to minimize iron deficiencies in poorly nourished population living in harsh environments. Some researchers have speculated that women who had hemochromatosis might have benefited from the additional iron absorbed through their diet because it prevented anemia caused by menstruation. This, in turn, led them to have more children, who also carried the hemochromatosis mutation. Even more speculative theories have suggested that Viking men may have offset the negative effects of hemochromatosis because their warrior culture resulted in frequent blood loss.

As the vikings settled the European coast, the mutation may have grown in frequency through what geneticists call the founder effect. When small populations establish colonies in unpopulated or secluded areas, there is significant inbreeding for generations. This inbreeding virtually guarantees that any mutations that aren’t fatal at a very early age will be maintained in large portions of the population.

Diagnosis of Hemochromatosis

A doctor will:

- ask about symptoms

- ask about any supplements you may take

- ask about personal and family medical history

- carry out a physical exam

- recommend some tests

The symptoms can resemble those of many other conditions, making diagnosis difficult. Several tests may be necessary to confirm a diagnosis.

Blood Test

A blood test, such as a serum transferrin saturation (TS) test, can measure iron levels. A TS test measures how much iron is bound to the protein transferrin, which carries iron in your blood.

A blood test can also give an idea about your liver function.

Genetic testing

DNA testing can show if a person has genetic changes that may lead to hemochromatosis. If there is a family history of hemochromatosis, DNA testing can be useful for those planning to start a family.

For the test, a healthcare professional may draw blood or use a swab to collect cells from your mouth.

Liver biopsy

The liver is the main place where the body stores iron. It is usually one of the first organs damaged by iron buildup.

A liver biopsy can show if there is too much iron in the liver or if liver damage is present. The doctor will remove a small piece of tissue from your liver for testing in a lab.

MRI tests

MRI scans and other noninvasive tests can also measure iron levels in the body. A doctor may recommend an MRI test instead of a liver biopsy.

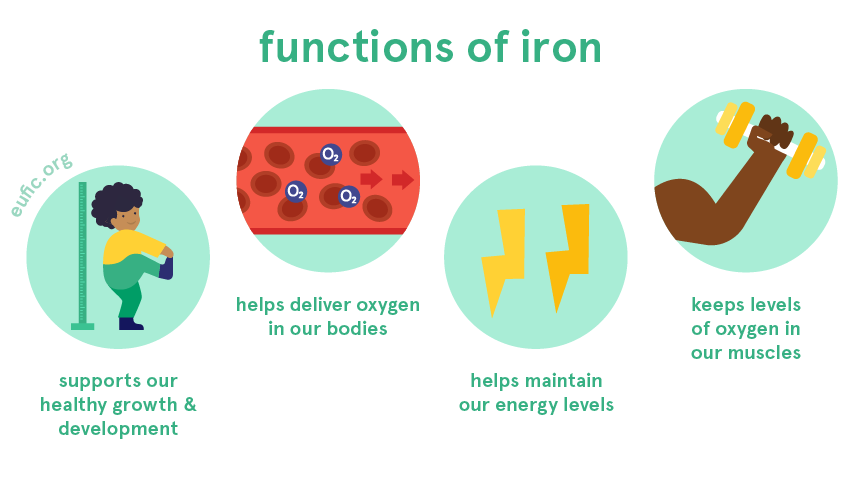

Importance of Iron for Human Body

Humans need iron for nearly every function of our metabolism. Iron carries oxygen from our lungs through the bloodstream and releases it in the body where it’s needed. Iron is built into the enzymes that do most of the chemical heavy lifting in our bodies, where it helps us to detoxify poisons and to convert sugars into energy. Iron poor diets and other iron deficiencies are the most common cause of anemia, a lack of red blood cells that can cause fatigue, shortness of breath, and even heart failure. As many as 20 percent of menstruating women may have iron-related anemia because their monthly blood loss produces an iron deficiency. That may be the case in as much as half of all pregnant women as well – they’re not menstruating, but the passenger they’re carrying is hungry for iron too. Without enough iron our immune system functions poorly, the skin gets pale, and people can feel confused, dizzy, cold and extremely fatigued.

Issue with Excess iron in Body

Food industry currently supplements everything from the flour to breakfast cereal to baby formula with iron. However, our relationship with iron is much more complex than it’s been considered traditionally that more iron consumption can only be better. Iron is essential – but it also provides a proverbial leg up to just about every biological threat to our lives. With very few exceptions in the form of a few bacteria that use other metals in its plate, almost all life on earth needs iron to survive. Parasites hunt us for our iron; cancer cells thrive on our iron. Finding, controlling, and using iron is the game of life. For bacteria, fungi and protozoa, human blood and tissue are an iron gold mine. Add too much iron to the human system and you may just be loading up the buffet table.

How Human Body act against excess iron

Human iron regulation is a complex system that involves virtually every part of the body. A healthy adult usually has between three and four grams of iron in his or her body. Most of this iron is in the bloodstream within hemoglobin, distributing oxygen, but iron can also be found throughout the body. Given that iron is not only crucial for our survival but can be potentially deadly liability, it shouldn’t be surprising that we have iron-related defense mechanisms as well.

We’re most vulnerable to infection where infection has a gateway to our bodies. In adult without wounds or broken skin, that means our mouths, eyes, noses, ears and genitals. And because infectious agents need iron to survive, all these openings have been declared iron no-fly-zones by our bodies. On top of that, those openings are patrolled by chelators – proteins that lock up iron molecules and prevent them from being used. Everything from tears to saliva to mucus – all the fluids found in those bodily entry points – are rich with chelators.

There is more to our iron defense system. When we’re first beset by illness, our immune system kicks into high gear and fights back with what is called the acute phase response. The bloodstream is flooded with illness-fighting proteins, and, at the same time, iron is locked away to prevent biological invaders from using it against us. It’s the biological equivalent of a prison lockdown – flood the halls with guards and secure the guns.

A similar response appears to occur when cells become cancerous and begin to spread without control. Cancer cells require iron to grow, so the body attempts to limit its availability.

Egg Whites effective against wound infections ?

Even some folk cures have regained respect as our understanding of bacteria’s reliance on iron has grown. People used to cover wounds with egg-white-soaked straw to protect them from infection. It turns out that wasn’t such a bad idea – preventing infection is what egg whites are made for. Egg shells are porous so that the check embryo inside can “breathe”. The problem with a porous shell, of course, is that air isn’t the only thing that can get through it – so can all sorts of nasty microbes. The egg white’s there to stop them. Egg whites are chock-full of Chelators (those iron locking proteins that patrol our bodies’ entry points) like ovoferrin in order to protect the developing chicken embryo – the yolk – from infection.

The relationship between iron and infection also explains one of the ways breast – feeding helps to prevent infections in newborns. Mother’s milk contains lactoferrin – a chelating protein that binds with iron and prevents bacteria from feeding on it.

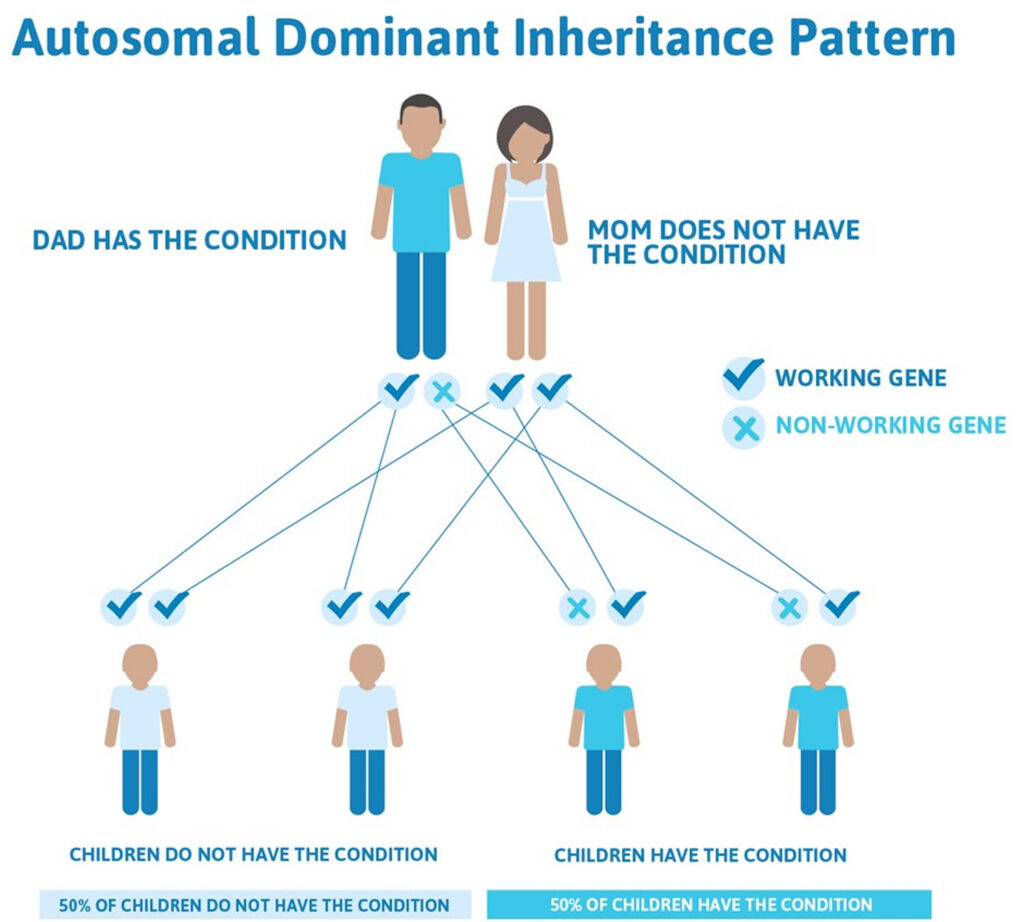

Why Hemochromatosis is Hereditary ?

Why would a disease so deadly be bred into our genetic code ? You see, hemochromatosis isn’t an infectious disease like malaria, related to bad habits like lung cancer caused by smoking, or a viral invader like smallpox. Hemochromatosis is inherited – and the gene for it is very common in certain populations. In evolutionary terms, that means we asked for it.

Remember how natural selection works. If a given genetic trait makes you stronger – especially if it makes you stronger before you have children – then you’re more likely to survive, reproduce and pass that trait on. If a given trait makes you weaker, you’re less likely to survive, reproduce, and pass that trait on. Over time, species select those traits that make them stronger and eliminate those traits that make them weaker. Now, what are the benefits of Iron loading that made Hemochromatosis a genetic disorder ?

In the past, healthy adult men were at greater risk than anybody else – children and the elderly tended to be malnourished, with corresponding iron deficiencies, and adult women are regularly iron depleted by menstruation, pregnancy and breastfeeding. Iron status used to mirror mortality. This may be one reason why human body accepted overload to iron to fulfill these iron needs of body. Which brings us full circle. Why would you take a pill that was guaranteed to kill you in forty years ? Because it will save you tomorrow. Why would we select for a gene that will kill us through iron loading by the time we reach what is now middle age ? Because it will protect us from a disease that is killing everyone else long before that.

Treatment of Hemochromatosis

Treatment is available for managing high iron levels.

Bloodletting (Phlebotomy)

Bloodletting or Phlebotomy is the treatment of choice for hemochromatosis patients. Regular bleeding of hemochromatosis patients reduces the iron in their system to normal levels and prevents the iron buildup in the body’s organs that is so damaging. It’s not just for hemochromatosis, either – doctors and researchers are examining phlebotomy as an aid in combating heart disease, high blood pressure, and pulmonary edema. New evidence suggests that, in moderation, bloodletting may have had a beneficial effect.

Bleeding also may help to fight infection by reducing the amount of iron available to feed an invader, providing an assist to the body’s natural tendency to hide iron when it recognizes an infection.

Chelation

Another option is chelation. This is a developing therapy that can help manage iron levels, but it is expensive and not a first-line treatment option. A doctor may inject the drugs or give you pills. Chelation helps your body expel excess iron in your urine and stool. However, there may be side effects, such as pain at the injection site and flu-like symptoms. Chelation may be suitable for people with heart complications or other contraindications for phlebotomy.

Lifestyle measures

Measures that can help you manage your health with hemochromatosis include:

- having annual blood tests to monitor iron levels

- avoiding multivitamins, vitamin C supplements, and iron supplements

- avoiding alcohol, which can cause additional damage to the liver

- taking care to avoid infections, for example, by having regular vaccinations and following good hygiene practices

- keeping a log of iron levels to monitor changes

- following all the doctor’s instructions and attending all appointments

- contacting your doctor if symptoms worsen or change

- asking your doctor about counseling if symptoms affect your quality of life