Malnutrition

Malnutrition, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), refers to deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients. It is well-known that maternal, infant, and child nutrition play significant roles in the proper growth and development, including future socio-economic status of the child. Reports of National Health & Family Survey, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, and WHO have highlighted that rates of malnutrition among adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and children are alarmingly high in India. Factors responsible for malnutrition in the country include mother’s nutritional status, lactation behaviour, women education, and sanitation. These affect children in several ways including stunting, childhood illness, and retarded growth. Although India has nominally reduced malnutrition over the last decade, and several government programs are in place, there remains a need for effective use of knowledge gained through studies to address undernutrition, especially because it impedes the socio-economic development of the country.

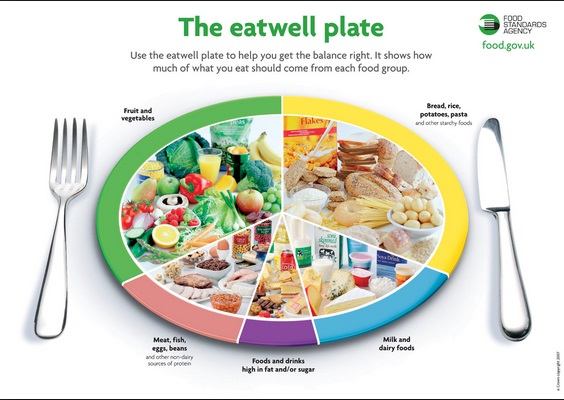

Malnutrition affects people in every country. Around 1.9 billion adults worldwide are overweight, while 462 million are underweight. An estimated 41 million children under the age of 5 years are overweight or obese, while some 159 million are stunted and 50 million are wasted. Adding to this burden are the 528 million or 29% women of reproductive age around the world affected by anaemia, for which approximately half would be amenable to iron supplementation. Many families can’t afford or access enough nutritious foods like fresh fruits and vegetables, legumes, meat and milk, while foods and drinks high in fat, sugar and salt are cheaper and more readily available, leading to a rapid rise in the number of children and adults who are overweight and obese, in poor as well as in rich countries.

In April 2016, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition from 2016 to 2025. The Decade aims to catalyse policy commitments that result in measurable action to address all forms of malnutrition. The aim is to ensure all people have access to healthier and more sustainable diets to eradicate all forms of malnutrition worldwide.

Introduction

Malnutrition in children is a public health problem in many developing countries. Apart from great human suffering, both physical and emotional, it is a major drain on the prospects for development in these countries. Why? Mainly because malnourished children require more intense care from their parents and are less physically and intellectually productive as adults. Being malnourished is also a violation of a child’s human rights. Lessons from the causes, and from government initiatives to manage and reduce child malnutrition in emerging economies, such as India, should be useful for other such countries wishing to diminish child malnutrition at home and to improve public intervention strategies.

In the South Asian region, India is one of the fastest growing countries economically, educationally, and technologically. Despite economic progress, India has failed to combat malnutrition that adversely affects the country’s socio-economic progress. More than one-third of the world’s malnourished children are in India. Half of the world’s malnourished children reside in 3 countries: Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

According to the Global Hunger Index 2017, India ranks 100 out of 119 countries. The prevalence of malnourished children in India is nearly double that in Sub-Saharan Africa and affects the mortality rate, productivity, and economic growth. Each year, nearly half of children in India are malnourished and almost a million children die before reaching one month of age. In India, 43% of children under 5 years are underweight and 48% are stunted, due to severe malnutrition (3 out of every 10 children are stunted).

Here are a few more statistics and information on the present situation :

– 19.8 million children below age 6 in India are undernourished (ICDS 2015)

– Only 9.6% of children between 6-23 months in the country receive an adequate diet

– 38% (1 in 3) of children between 0-5 years are stunted in the country

– 21% (1 in 5) of the children in the country suffer from wasting

– 36 % of children under age 5 are underweight in India

– 58% of children between 6 months – 5 years were found to be anaemic in the country

– Total immunisation coverage in the country stood at 62% in 2015-16

– 21% of the births in the country were home births

– Only 21% of mothers (1 in 5) received full antenatal care in the country

– More than 50% of the pregnant women aged 15-49 years were found to be anaemic

Various government initiatives have been launched over the years which seek to improve the nutrition status in the country. These include the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), the National Health Mission, the Janani Suraksha Yojana, the Matritva Sahyog Yojana, the Mid-Day Meal scheme, and the National Food Security Mission, among others. However, concerns reagarding malnutrition have persisted despite improvements over the years.

Classification of Malnutrition

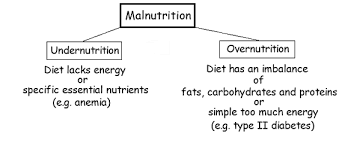

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ‘malnutrition’ refers to deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients. It can be either ‘undernutrition’ or ‘overnutrition’. Symptoms of malnutrition include physical and mental exhaustion, low weight in relation to height (wasting) and shortness for age (stunted), diminished skin folds, exaggerated skeletal contours, and loss of elasticity of skin.

The WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition uses a Z-score cut-of point of <−2 SD to classify low weight-for-age, low height-for-age, and low weight-for-height as moderate and severe undernutrition, and <−3 SD to define severe undernutrition. The cut-of point of >+2 SD classifies high weight-for-height as overweight in children.

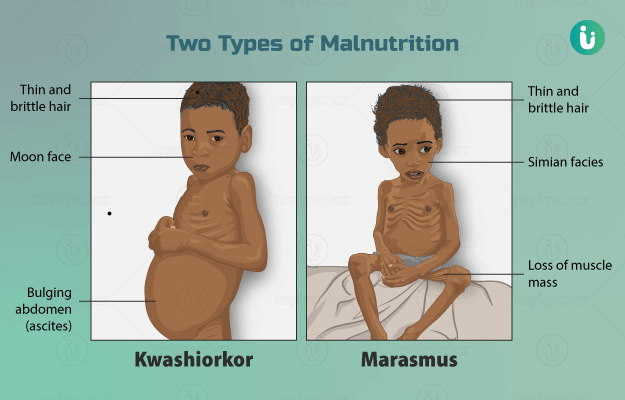

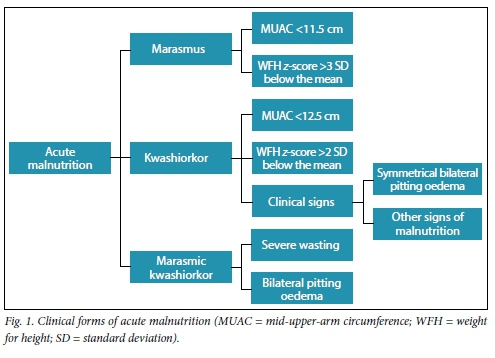

The most widely studied malnutrition consequences include marasmus and kwashiorkor, both consequences of lack of proteins and energy. Protein–calorie malnutrition (PCM) occurs as marasmus (characterized by growth failure and wasting) and as kwashiorkor (only protein deficiency), characterised by tissue oedema and damage. Both kwashiorkor and marasmus are common in infancy and child hood when dietary essential amino acid content is insufficient to satisfy growth requirements. Kwashiorkor typically occurs at about age 1, after infants are weaned from breast milk to a protein-deficient diet of starchy gruels or sugar water, but it can develop at any time during the formative years. Marasmus affects infants aged 6–18 months as a result of breastfeeding failure or when there exists chronic diarrhoea.

| Classification | Definition | Grading | |

| Gomez | Weight below %age Median WFA (weight for age) | Mild (Grade 1) Moderate (Grade 2) Severe (Grade 3) | 75%-90% WFA 60%-74% WFA <60% WFA |

| Waterlow | z-scores (SD – standard deviation) below median WFH (weight for height) | Mild Moderate Severe | 80-90% WFH 70-80% WFH <70% WFH |

| WHO (wasting) | z-scores (SD – standard deviation) below median WFH (weight for height) | Moderate Severe | -3%</=z-score < -2Z-score < -3 |

| WHO (stunting) | z-scores (SD – standard deviation) below median HFA (height for age) | Moderate Severe | -3%</=z-score < -2Z-score < -3 |

| Kanawati | MUAC divided by occipitofrontal head circumference | Mild Moderate Severe | <0.31 <0.28 <0.25 |

| Cole | Z-scores of BMI for age | Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 | BMI for ageZ-score < -1BMI scorescore < -2BMI scoreZ-score < -3 |

Factors responsible for Malnutrition

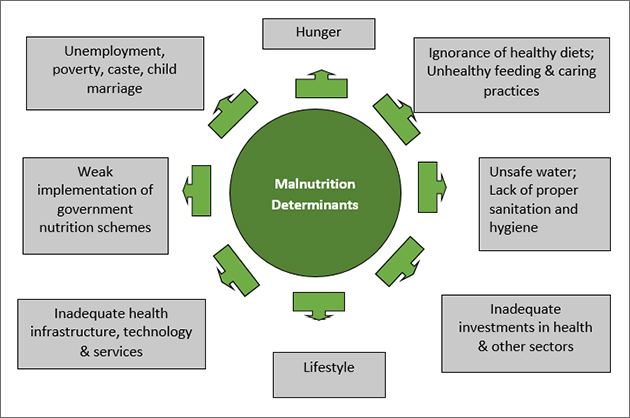

Various factors play pivotal roles in causing chronic malnutrition in children. One of the most important is the mother’s nutritional status. About 36% of the population of women are underweight, and 56% of women and 56% of adolescent girls between 15 and 19 years old suffer from iron deficiency anaemia due to undernourishment in India. A staggering 75% of new and adolescent mothers are anaemic and most put on less weight during pregnancy than they should — only 5 kg on average, compared to the worldwide average of close to 10 kg. Between 2005–2006 and 2015–2016, there was an average decrease of only 3.5 percentage points in iron deficiency anaemia.

Eight states failed to reduce their burdens (Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala, Meghalaya, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh).

Data on anaemia showed that 56% of girls and 30% of boys aged 15–19 years were anaemic. Menstrual blood loss makes adolescent girls more vulnerable to the problem of iron deficiency anaemia (IDA). This gender difference results from gender inequality that is seen even in middle-income families, though it is more prevalent in poorer families. Adolescent girls are less likely than boys to consume food rich in proteins, vitamins, and micronutrients. The NHFS-4 reported only 2% decline of iron deficiency anaemia among women from 55% in 2005–2006 to 53% in 2015–2016, with 51% and 54% women with anaemia in urban and rural areas, respectively. And in 8 states, over 60% of women were anaemic. Anaemia in children under 2 years of age affects brain function and folate deficiency causes neural tube defects.

Pregnant women and lactating mothers suffer most from malnutrition and this may be the cause of prematurity and low birth weight babies. Studies indicate a close association of maternal nutritional status with the well-being of a child. Women malnourished in childhood due to poverty or gender inequality are most likely to have unhealthy babies. According to UNICEF data, one-third of women in India in their reproductive period are malnourished and give birth to malnourished babies; this pattern perpetuates through generations.

In India most mothers lack knowledge about how to feed children to improve nutritional status. Growing evidence suggests that lack of breastfeeding or a reduced breastfeeding period may lead to undernutrition in infants and children. This is especially critical during the first 6 months of a child’s life. Breastfeeding increases immunity in babies and research shows an association between limited or no breastfeeding and death of children under 5 years. Breastfeeding protects against infections during and most likely after lactation, as well as possibly against certain immunologic diseases, including allergy. A few factors in milk, including anti-antibodies (anti-idiotypic antibodies) and T and B lymphocytes, together with transfer of numerous cytokines and growth factors via milk, may add to an active stimulation of the infant’s immune system. Consequently, the infant might respond better to both infections and vaccines.) Short intervals between pregnancies also contributes to nutritional deficiency in children. Studies show that malnourished girls, early marriage, and early conception contribute to malnourished babies or low birth weight babies who are less competent.

In developing countries, women education plays a prominent role in reducing malnutrition. Analysis of National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-3 data indicates that education of women is directly proportional to reduction in the percentage of malnutrition and early marriage. Education has shown a significant contribution to the reduction of child underweight, from 43% to 15.5% in developing countries.

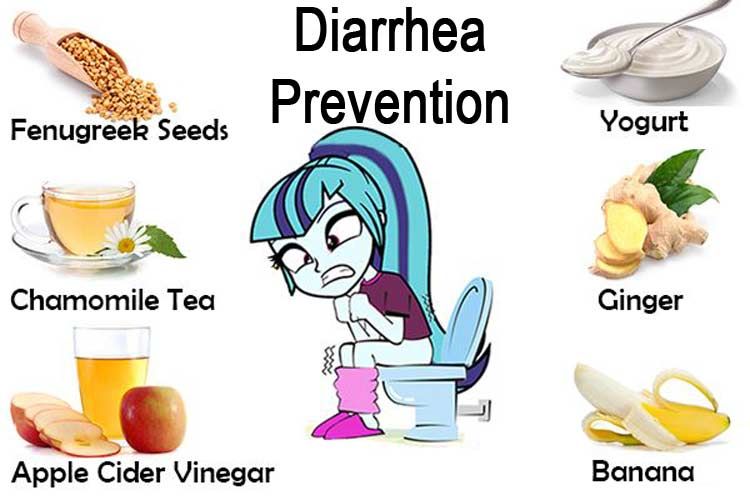

Another important contributing factor for malnutrition in India is poor sanitation. It causes diseases including diarrhoea and malaria through pathogens, thus reducing consumption of nutritious foods and resistance to disease in children. According to World Health Organization estimates, 50% of malnutrition is due to diarrhoea or intestinal infection given poor sanitation. Defecating in the open may be one of the reasons for intestinal infection apart from using contaminated water. In India, approximately 620 million people use public toilets or defecate outside. Malnutrition in children can be caused due to infection through drinking water as infections reduce the absorption of nutrients. (Poor sanitation leads to possibility of water pooling, which due to infux of garbage and refuse, becomes the perfect environment for mosquitoes to breed and transmit malaria.)

Effects of Malnutrition on Children

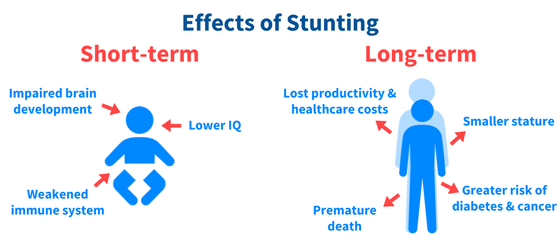

As described earlier, the predominant effects of malnutrition are low weight, stunted growth, and muscle wasting. About 48% of Indian infants under 5 years of age are reported to suffer from stunted growth due to malnutrition. Malnutrition increases the risk for infectious diseases by weakening the immune system and also impairs cognitive and motor functions in growing children. These children die from childhood conditions like diarrhoea, and illnesses including tuberculosis, measles, pneumonia, and malaria.

Studies show that the last few months of gestation and first 2 years of life after birth are critical for growth and development of babies. The first 1000 days (conception to 2 years post-partum) are considered a ‘window of opportunity’ for addressing malnutrition. Severe malnutrition is also known to influence metabolic and organ function as well as children’s behaviour. About one-third of deaths in children under age 5 years are attributed to undernutrition. India’s data for 2015–2016 showed stunted growth in 38% of children under 5 years; 21% to be ‘wasted’; 36% to be ‘underweight’; and 58% between 6 and 59 months to be anaemic.

The Global Hunger Index 2016 Report showed a relationship between malnutrition and retarded growth. Malnourished children are found to have low resistance to infection and are thus more prone to diseases that ultimately influence economic growth of the country.

Treatment of Malnutrition

In response to child malnutrition, ten steps are recommended for treating severe malnutrition. They are to prevent or treat dehydration, low blood sugar, low body temperature, infection, correct electrolyte imbalances and micronutrient deficiencies, start feeding cautiously, achieve catch-up growth, provide psychological support, and prepare for discharge and follow-up after recovery.

Among those who are hospitalized, nutritional support improves protein, calorie intake and weight.

Food

The evidence for benefit of supplementary feeding is poor. This is due to the small amount of research done on this treatment.

Specially formulated foods do however appear useful in those from the developing world with moderate acute malnutrition. In young children with severe acute malnutrition it is unclear if ready-to-use therapeutic food differs from a normal diet. They may have some benefits in humanitarian emergencies as they can be eaten directly from the packet, do not require refrigeration or mixing with clean water, and can be stored for years.

In those who are severely malnourished, feeding too much too quickly can result in refeeding syndrome. This can result regardless of route of feeding and can present itself a couple of days after eating with heart failure, dysrhythmias and confusion that can result in death.

Micronutrients

Treating malnutrition, mostly through fortifying foods with micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), improves lives at a lower cost and shorter time than other forms of aid, according to the World Bank. The Copenhagen Consensus, which look at a variety of development proposals, ranked micronutrient supplements as number one.

In those with diarrhea, once an initial four-hour rehydration period is completed, zinc supplementation is recommended. Daily zinc increases the chances of reducing the severity and duration of the diarrhea, and continuing with daily zinc for ten to fourteen days makes diarrhea less likely recur in the next two to three months.

In addition, malnourished children need both potassium and magnesium. This can be obtained by following the above recommendations for the dehydrated child to continue eating within two to three hours of starting rehydration, and including foods rich in potassium as above. Low blood potassium is worsened when base (as in Ringer’s/Hartmann’s) is given to treat acidosis without simultaneously providing potassium. As above, available home products such as salted and unsalted cereal water, salted and unsalted vegetable broth can be given early during the course of a child’s diarrhea along with continued eating. Vitamin A, potassium, magnesium, and zinc should be added with other vitamins and minerals if available.

For a malnourished child with diarrhea from any cause, this should include foods rich in potassium such as bananas, green coconut water, and unsweetened fresh fruit juice.

Diarrhoea

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends rehydrating a severely undernourished child who has diarrhea relatively slowly. The preferred method is with fluids by mouth using a drink called oral rehydration solution (ORS). The oral rehydration solution is both slightly sweet and slightly salty and the one recommended in those with severe undernutrition should have half the usual sodium and greater potassium. Fluids by nasogastric tube may be use in those who do not drink. Intravenous fluids are recommended only in those who have significant dehydration due to their potential complications. These complications include congestive heart failure. Over time, ORS developed into ORT, or oral rehydration therapy, which focused on increasing fluids by supplying salts, carbohydrates, and water. This switch from type of fluid to amount of fluid was crucial in order to prevent dehydration from diarrhea.

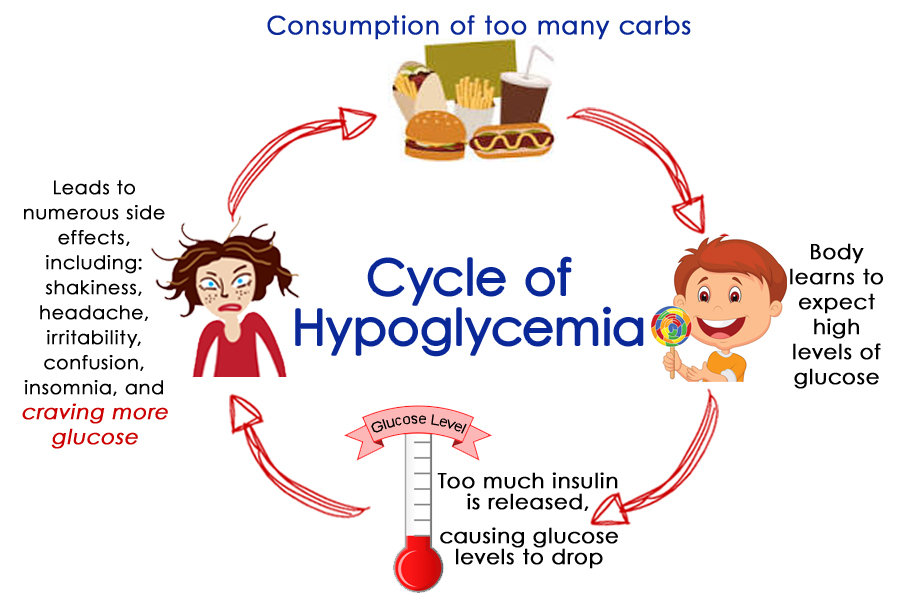

Low Blood Sugar

Hypoglycemia, whether known or suspected, can be treated with a mixture of sugar and water. If the child is conscious, the initial dose of sugar and water can be given by mouth. If the child is unconscious, give glucose by intravenous or nasogastric tube. If seizures occur after despite glucose, rectal diazepam is recommended. Blood sugar levels should be re-checked on two hour intervals.

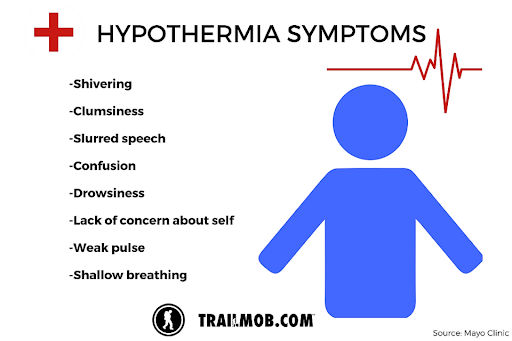

Hypothermia

Hypothermia can occur. To prevent or treat this, the child can be kept warm with covering including of the head or by direct skin-to-skin contact with the mother or father and then covering both parent and child. Prolonged bathing or prolonged medical exams should be avoided. Warming methods are usually most important at night.

Management

Many management measures have been already implemented by the Government of India to address nutritional status including, reducing poverty, improving sanitation, fortifcation of foods with essential nutrients, enhancing women’s education, and improving agricultural practices.

Article 47 of Indian Constitution states that “The duty of the state is to raise the level of nutrition and living standards and to improve public health”. Because the Indian Government has accorded high priority to malnutrition, it is implementing several programs through multiple Ministries or Departments of the national government, through State Government or Union Territory Administration (President of India appoints an administrator or Chief Minister) to improve the nutritional situation in India.

Policy and Programmatic initiatives

Among developing countries, India has been in the forefront for developing national food and nutrition databases (such as the Indian Food Composition Tables, 2017) and undertaking research studies and surveys documenting agriculture, food, and nutrition transitions. The country has also used the evolving knowledge and invested in nutrition intervention programmes to

- improve food and nutrition security of its citizens,

- ensure that the ongoing food supplementation programs provide sufficient food to meet the energy/nutrients gap in vulnerable segments of population,and

- improve ongoing nutrition interventions, converge existing programs and introduce newer ones, all aimed at preventing, early detection, and effective management of child undernutrition in the country.

The following programs and schemes have been implemented for improving nutrition and combating malnutrition by the Government of India.

Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS)

One of the most comprehensive schemes for child development, started by the Ministry of Women and Child Development in 1975, is funded partly by the Central government of India and partly by the UNICEF. Its aim is to provide food and primary health care to preschool children under 6 years of age and to their mothers.

To implement it, India established ‘Anganwadi centres’ in rural areas. India launched ICDS in accordance with the National Policy for Children in India to fight malnutrition, ill-health, and to address gender inequality. Anganwadi centres provide immunisations, health check-ups, nutritious food, and informal education under this scheme, spending annually on average US$10–22/child. Supplementary Nutrition is one of the six services provided under the ICDS. It is intended primarily to bridge the gap between the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) and the Average Daily Intake (ADI). ICDS is provided to children (6 months – 6 years) and pregnant and lactating mothers.

In 2010, India launched another program, “Pradhan Mantri Matritva Vandana Yojana (PMMVY)”. (Previously it was called “Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana (IGMSY)”.) The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) launched it as part of ICDS after the Evaluation of ICDS Report in 2011 called for improving the nutrition of pregnant mothers. This maternity benefit program is a cash transfer scheme for pregnant and lactating women of 19 years of age or above for the first live birth. It provides partial wage compensation to women for wage-loss during childbirth and childcare. In 2013, India placed the scheme under the National Food Security Act (2013) to provide a cash maternity benefit of US$87. Studies suggest, however, that eligibility and other conditions exclude a large number of women from receiving their entitlements.

There is need for the ICDS program to be redirected towards the younger children (0–3 years) and the most vulnerable population segments in states and districts with greater prevalence of undernutrition. It would be prudent to consider emphasizing infant and young child feeding and maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation. Doing so could bridge the gap between the policy intentions of ICDS and its actual implementation. Many of these gaps in the ICDS, including the IGMSY, can be filled with a regular schedule of workshops and through sensitization to the importance of preschool nutrition, for the Anganwadi centre staff, pregnant and lactating mothers, mothers with children under-5 years age and school going children, and teachers of primary schools.

Midday Meal Scheme (MDM)

In 1995, the Central Government started the National Programme of Nutritional Support to Primary Education, popularly known as the Mid-Day Meal scheme (MDM), to improve the nutritional status and enhance enrolment and school attendance of children. Implementation of MDM has been successful throughout the country.

The Public Report on Basic Education (PROBE) reported that the mid-day school meal increased nutritional status of school children. However, it also called for a transparent administrative system and improvement in cooking methods — mainly because many of the school mid-day meal contracts were given arbitrarily to self-help groups or organisations without following due diligence and the cooking methods vary across the country.

National Health Mission (NHM)

Launched in 2005, the National Health Mission covers both the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) and aims to enhance the health programmes and health service delivery, in both rural and urban areas, by improving maternal, neonatal child and adolescent health, thus preventing diseases. The Mission also has a component of ‘convergence’ for addressing prevention, identification, and management of malnutrition in children. It is being implemented by ICDS and the Ministry/Department of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. Most of the primary health centres, however, face severe shortages of doctors and trained para-medics, lack infrastructure, and lack supplies of many essential drug and vaccines.

National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013

Launched on 10 September 2013, the National Food Security Act (2013) is an Act of the Parliament of India intended to provide subsidized food grains to approximately two-thirds of India’s 1.2 billion people. Under the Act, beneficiaries of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) are entitled to 5 kilograms per person per month of cereals at subsidized prices (USD 0.05/kg for rice, USD 0.03/ kg for wheat, and USD 0.02/kg for coarse grains). The TPDS covers 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population.

Another program under this Act, the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY), launched in December 2000, provides support to populations with fewest resources. They (known as the Poorest Families category) are entitled to receive 35 kg of food grains per month at the subsidized rate under the scheme of AAY. This scheme is less successful due to limited resources, an exponentially increasing population, lack of infrastructure, operational inefficiencies, and poor performance of the public distribution system.

Villlage Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee (VHSNC)

The Government of India launched the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in April 2005. The Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee (VHSNC, earlier known as Village Health and Sanitation Committee) is a major initiative to Malnutrition in India: status and government initiatives decentralise and empower local people to improve sanitation and nutrition in villages. It allows ‘panchayats’ (village councils) to contribute to the governance of health and other public services in villages. The VHSNCs monitor the work and contribution of community health workers, such as Anganwadi Workers (AWW), Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), and other public staff (from government entities such as the Water and Sanitation department, Roads work, among others) in order to maintain good sanitation and healthy environments in the villages. These government health staff work under the supervision and monitoring of the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRI).

Members of a VHSNC require orientation about their roles and responsibilities, technical aspects of health, nutrition, sanitation, and participatory processes related to making plans and using funds. VHSNCs need assistance to plan effectively to allocate their funds rationally among health, nutrition, and sanitation activities in the community.

ASHAs and ANMs are responsible for providing information on malnutrition status of children (under 6 years of age) in their target areas to the committee. They are also responsible for providing an interface between villagers and the public health care system. And they are accountable for ensuring take-home rations for children under 3 years and for pregnant/lactating mothers. For children aged 3–6 years, ANMs provide supplementary food and raise issues about lapses in supplies of supplementary foods with the committee (VHSNC). The VHSNC ensures that the Anganwadi Centres (AWC) provide hot-cooked meals in accordance with set norms. There are no standard practices of regular food inspection and there is need for food inspectors to upload online reports, along with pictures of products, for monitoring the delivery of these meals to the higher authorities.

Food Safety and Standard Authority of India (FSSAI)

Established by Government of India on 5 September 2008 under the Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006, the FSSAI provides technical support and scientific advice to the government for policy and programme on food safety and nutrition. It also supplies micro-nutrients to fortify foods and trains school staff to prepare mid-day meals to fortify the food for children. In the Gajapati District of Odisha State (India), for example, FSSAI trains school staff to fortify rice with iron.

Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls (RGSEAG) or Sabla Scheme

The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) started implementation of SABLA for the Government of India on 1 April 2011. SABLA is also known as “Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent Girls (RGSEAG). Its aim is to empower adolescent girls aged 11–18 years by promoting awareness about health, nutrition, adult reproductive and sexual health (ARSH), providing education in life skills and family welfare. It also provides iron and folic acid supplements under Reproductive and Child Health (RCH-2) and National Rural Health Mission (NRHM).

SABLA replaced Kishori Shakti Yojana (KSY) (that aimed to improve the health and nutritional status of girls in the age group of 11–18 years) and Nutrition Programme for Adolescent Girls (NPAG) (that provided 6 kg of free food grain to under nourished adolescent girls). The AWW need more frequent training and experience sharing exercises to learn from one another about overcoming challenges, as the counselling components are quite demanding of their time.

Village Health Nutrition Day (VHND)

One day every month, ASHA, ANM, and AWW mobilise villagers, especially women and children, at Anganwadi Centres (AWC) to meet health personnel to learn about healthcare facilities and to gather information on maternal and child health, nutrition, family planning, sanitation, and communicable diseases. This day also provides opportunities to vaccinate children (including school dropouts), to treat those with tuberculosis (TB) and other diseases, and to distribute condoms and oral contraceptive pills as part of family planning. This day would also prove beneficial to villagers if it could be strengthened to effectively deliver drugs, to ensure prevention of communicable diseases, and to educate about family planning, growth monitoring, care during postnatal period, water, and sanitation facilities. Improved participation of Panchayat members could ensure greater community participation thus contributing to its effectiveness.

Initiatives by National Nutrition Mission Programs for Future Management

NNM monitors, supervises, fixes targets, and guides the nutrition-related interventions across the Ministries. It will strive to reduce stunting, undernutrition, anaemia, and low birth weight babies.

It aims to create synergy, ensure better monitoring, issue alerts for timely action, and encourage States/UTs to perform, guide, and supervise the line Ministries and States/UTs to reach the goals. The strategy for implementing this begins at the grassroots level and is based on intense monitoring for compliance with the Convergence Action Plan. The Convergence Action Plan aims to link the various services provided at different growth stages of pregnancy and early child life including the crucial intervention packages available for the first 1000 days of childbirth and pre and post-delivery support to mothers provided by different Departments/Ministries (such as PMMVY, ANC, PNC, Home visits of ASHA/AWW, Vaccination, etc.), and also at State/Union Territory, District, and Block levels. NNM has three phases from 2017–2018 to 2019–2020. Its targets include reducing stunting, undernutrition, anaemia (among young children, women, and adolescent girls) and low birth weight by 2, 2, 3, and 2% per year, respectively. Although the target to reduce stunting is at least 2% p.a., the mission would strive to achieve reduction in stunting from 38.4% (NFHS-4) to 25% by 2022.

Conclusion

Among the developing countries, India has one of the highest numbers of malnourished children. Nearly half of all children in India are malnourished and each year almost a million children die before one month of age. Many new mothers are adolescents, most of whom are anaemic. Compared to the global average, these mothers gain only half as much weight during pregnancy. Maternal and child mortality and malnutrition rates in India are also alarmingly high. Sixty million children are too short for their ages and half of those are too thin (acutely malnourished). Prevalence of undernutrition is still very high in India despite reduction, according to UNICEF, from 40 to 29% between 1990 and 2009.

In comparison with developing countries with similar health profiles India fares well in terms of infant mortality rate (IMR) and under five mortality rate (U5 MR). India fares poorly when underweight in under-5 children is used as an indicator for food security with rates comparable to that of Sub-Saharan Africa. Over the last few years, the Government of India has recognised this and has expanded, consolidated—and also introduced various programs to combat child malnutrition. There still exist some issues and challenges with these interventions. Even so, awareness of these interventions and some lessons derived from them can be useful for countries that are poised to improve child malnutrition in similar settings.